Waste in your injection molding process is a bad thing: that’s news to no one. As an injection molding manufacturer, of course you’re always trying to increase efficiency and reduce the amount of waste that goes into (and is produced by) any process. Yet too often, the idea of “waste” is only looked at on the surface — only as, for example, the amount of material waste in a process. In reality, there are many types of waste that can be present in manufacturing. They can all affect your production efficiency, costs (for you and your customers) and bottom line.

If you’re familiar with lean manufacturing or have investigated different types of waste in the past, you may have heard the acronym “TIMWOOD.” It’s become something of an industry-standard way of remembering the seven main types of waste that may be present in production. Below, we’ll go through each letter of the acronym, and include some pointers on how each type of waste can be addressed or reduced.

It’s worth remembering that in lean manufacturing — the framework in which these types of waste became codified and widely recognized — the concept of “waste” refers to any facet of the process that does not lead directly to value. Under this definition, the idea of “waste” is very strict. In fact, almost every part of the process can be defined as “waste,” unless perfection is achieved (which is, of course, impossible). Thus, rather than trying to completely do away with any areas of waste that you may identify, focus instead on improving as much as you can. Even incremental improvements can, over time, have a tangible effect.

Seven Ways To Identify And Reduce Waste In Injection Molding

T: Transportation

Transportation waste refers to unnecessary or excess movement of resources (materials, equipment, workers, etc.) from one stage of the production process to another. Below, you’ll see that another type of waste is “motion,” and these two can be easily confused. A good way to remember the difference is to think of transportation waste as occurring between processes, while motion waste occurs within a process, or while a process is happening. (More on that shortly.)

Transportation waste refers to unnecessary or excess movement of resources (materials, equipment, workers, etc.) from one stage of the production process to another. Below, you’ll see that another type of waste is “motion,” and these two can be easily confused. A good way to remember the difference is to think of transportation waste as occurring between processes, while motion waste occurs within a process, or while a process is happening. (More on that shortly.)

Transportation waste can occur within your facility. For instance, storing injection molding material in a different area than where the machinery is located. It can also have a much wider scope, such as talking about your supply chain or the geographic location of your distributors. When you attempt to reduce transportation waste, you address two issues:

- Wasted time and resource effort in physically moving materials or people farther than is required.

- Increased risk of calamity in the course of this unnecessary transportation. For example, accidents or damaged materials or equipment.

What can you do? Review as many aspects of the movement of people, parts and materials as possible. Are there hidden inefficiencies, such as saving money on material costs by choosing a supplier that is located much farther away? Take a holistic look at your facility’s floorplan: Is there a logical “flow” or layout of resources that creates as much efficiency as possible? Taking the time to carry out these steps can pay off in the long run.

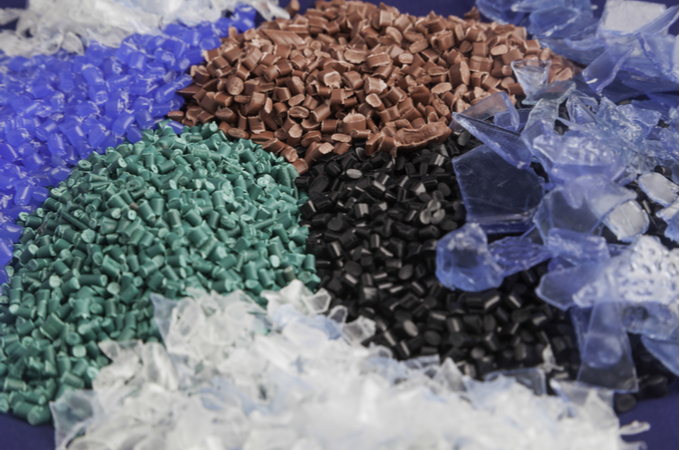

I: Inventory

With inventory waste, you should look at any excess material or product that you’re storing as an inefficient use of space and resources. In the context of waste as a lack of value, it makes sense: Inventory that’s just sitting there — whether it’s raw material not in use, partially finished product awaiting finishing or packaging, or completed production runs that haven’t yet been shipped — isn’t being directly used as something that will get either you or your customer paid, and thus is wasteful.

What can you do? Look at the reasons why you might have excess inventory on hand: Are their inefficiencies or breakdowns between processes? Have you optimized your supply chain, ordering and fulfillment?

M: Motion

As mentioned above, “motion” waste refers to non-essential movement within a process — whether of material, equipment, people or product. For example, is your cycle time as low as it can be? Are injection and holding times set to the minimum required for your selected material? A key component of motion waste is unnecessary movement by people. For instance, too much turning (to reach or move equipment) or bending. Reducing unnecessary motion by people can help cut down on injuries and create a more effective work environment.

What can you do? Review your processes and equipment layout to identify and rectify any unnecessary areas of motion. It can also help to solicit feedback from employees on the floor — those who are actually engaged in these processes and are likely best able to identify inefficiencies.

W: Waiting

Waste due to waiting can occur for any number of reasons, but they all add up to downtime. Waiting waste can occur if material is waiting to be fed into a machine, if machines are idle and waiting for employees to operate them, if damage to equipment or molds means that processes can’t be run, and so on. As you’re likely starting to see, many of these areas of waste dovetail together: For instance, waiting can also tie into excess inventory.

What can you do? Take a high-level look at shift scheduling and timing of processes, for example. Has everything been looked at as a whole, in order to cut down on waiting time? Or, is each process siloed to meet “small picture” concerns — thus, not working as an efficient part of the whole?

O: Overprocessing

Every project has a minimum set of acceptable specifications — likely from the customer, as well as to meet your own quality and production standards. If you’re going beyond these specifications, you’re creating waste due to overprocessing. These are unnecessary elements of the process that do not add value for you or the customer, since they are neither requested nor required. Overprocessing examples can include working to tighter tolerances than required, or adhering to unnecessarily stringent part acceptance standards.

Every project has a minimum set of acceptable specifications — likely from the customer, as well as to meet your own quality and production standards. If you’re going beyond these specifications, you’re creating waste due to overprocessing. These are unnecessary elements of the process that do not add value for you or the customer, since they are neither requested nor required. Overprocessing examples can include working to tighter tolerances than required, or adhering to unnecessarily stringent part acceptance standards.

What can you do? Your quality standards should never be compromised. However, that doesn’t mean that you need to go beyond what the customer has requested (provided parts will be produced safely and effectively).

O: Overproduction

Overproduction waste is just what it sounds like: producing more parts than is necessary. This might occur because you’re anticipating more orders, or because a mold has more cavities than the number of parts that has been ordered — among many other reasons. Once again, this issue ties into excess inventory — in addition to the inefficiency and waste of running processes to produce parts with no identified customer or buyer.

What can you do? Understand that any perceived benefits of excess inventory are far outweighed by the waste that it produces — storing it, moving it and (perhaps) disposing of it at some point. Tailor your processes and production runs so that you’re only producing as many parts as have been ordered.

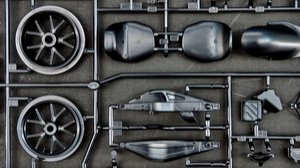

D: Defects

Defect waste is likely something with which you’re familiar: rejected parts due to errors in production, machine and tool damage or maintenance problems, and simple human error. Defects are one of the most common and obvious types of waste in injection molding. Yet that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways to reduce these errors.

What can you do? Sufficient employee training and retraining is one of the most effective tools at your disposal to reduce product defects. You should also ensure that processes, equipment and materials all have sufficient documentation to let employees do their jobs effectively and knowledgably.

Even if you’re familiar with the “TIMWOOD” list of areas of waste in injection molding, it’s still worth your time to take a close look at your processes and people in order to ensure that you’re experiencing as few inefficiencies as possible — especially if it’s been a while since you’ve last done so. Even small tweaks and improvements can have a lasting effect. Ultimately, helping to create a culture of quality and efficiency throughout your facility.