Although 3D printing has been around for thirty years, its medical applications have only been around for half that time.

It all started when, in 2000, a bioengineer named Thomas Boland modified an old inkjet printer so that it would print living cells instead of standard printer ink. Further modifications to the printer made it possible for the tray to move up and down along the Z-axis to print the cells on top of each other in layers—this is what makes it three dimensional instead of just a single layer of cells in a funny shape.

Right now, scientists are able to 3D print layers of cells into tissues. Although these tissues still aren’t quite ready to be transplanted into a living body, they can be used to test new treatments and medicines. According to Organovo, the 3D tissues respond in a more lifelike way than traditional 2D tissue samples.

Scientists are looking ahead to 3D printing whole organs for transplant. Although early attempts have not been completely successful, a few experiments have earned public interest: one researcher created miniature kidneys that can live up to four months in a lab. Obviously this isn’t worthy of the same praise as the creation of a full-sized, functional 3D organ, but it’s still an extremely important step on the path to having transplantable organs on demand…which is good news for the nearly 125,000 people on the organ donation waiting list.

There are, of course, some challenges associated with the 3D printing of human tissues or organs. When doing a transplant of any kind, contamination of the organ is a concern. When that organ has been grown in a lab, it can be contaminated at any point in the growing process, and any contamination can be deadly to a patient.

There’s also a challenge in creating organs that have blood vessels. While an organ needs them to survive in a human body, they are not developed in a lab where tissues are nourished through what’s called a growth medium. Scientists need to overcome this hurdle in order to make an organ that can be successfully implanted in a human body.

A different way researchers and medical professionals can use 3D printing to improve patients’ lives now is by creating implants to help those with hearing difficulties. The patient can be scanned to get precise measurements for a hearing aid or cochlear implant. These scans are used to print a device that is perfectly formed to the patient’s needs. A hearing aid that’s 3D printed will fit perfectly in their ear without the patient suffering from pain or loss of usefulness because of a loose fit.

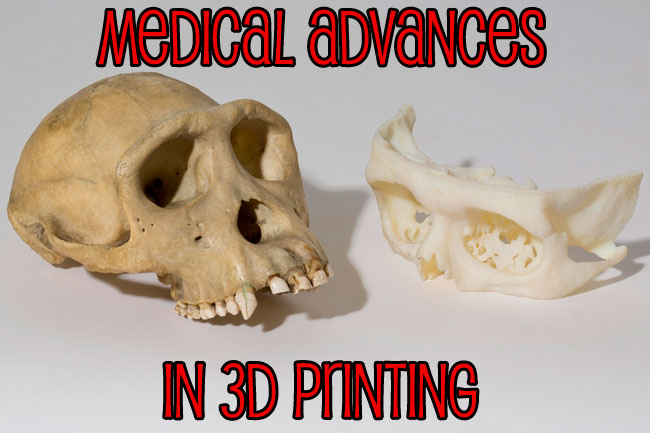

3D printing can also be used for dental applications—anything from crowns to bridges to corrective models. Without 3D printing, it can take weeks for dental appliances to be created, leaving patients with uncomfortable temporary applications. With 3D printing, the time to create dental models can be cut down drastically to the next day or just a couple of hours.

One application of 3D printing that gets a lot of attention is its usefulness in prosthetic limbs. Traditional prosthetics can cost anywhere from $5,000 to $40,000 and often have to be replaced after a few years. 3D printed prosthetics, however, can be made for just a fraction of the cost: replacing a few fingers on a hand can cost just $10. 3D printed prosthetics also tend to be more functional than traditional prosthetics as they can be created with moving parts. This is an excellent option for children who quickly outgrow their prosthetics.

There have even been some 3D printed prosthetics made for animals: Turbo-Roo received a 3D printed cart, and Derby received more traditional-looking prosthetics for his front legs.

So where will medical advances in 3D printing go in the future? Certainly we’ll see a more competitive market as these processes become more mainstream—its applications will become faster and cheaper as the technology advances—and traditional manufacturers will have to find a way to compete.

And although 3D printed organs aren’t quite ready yet, researchers are still fighting to find a way to make them possible, and in a few years maybe we’ll see them saving lives.